"The unrecorded past is none other than our old friend, the tree in the primeval forest which fell without being heard."

a blog about history, i.e. life

Five

In which we celebrate Independence Day in Independence. I learn more about life and death and Richie Scudder. Robin returns and I’m so happy and then I’m not.

Already before noon on the Fourth of July, the shimmering air was smoky with firecrackers and Black Cats. It was as hot as the inside of a cow and every bit as humid. Mama decided that she’d stay home with the little kids. She’d put a wet washcloth on her head and take a nap in front of the window fan, something she’d been doing more and more of here lately.

Dad could hardly touch the steering wheel without burning his fingers. He pulled his ball cap low over his eyes and shook his head at Jimmy. “Honey, you gotta wear those durned corduroys today?”

“I’m not too hot, Dad. Honest.”

If I were a mean person, which I’m NOT, I would say he wore those long britches so no one would see his pudgy white legs.

“Okay, kiddo,” Dad said. “To each his own.”

“Dad?”

“Yeah, son?”

“Did you know that exactly one hundred years ago today was when they just got done fighting the biggest battle ever in the whole western hemisphere? In the Civil War? It was at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in eighteen-sixty three.”

Dad rubbed at his pointy nose. “Wahoo! Is that right?”

Jimmy grinned. “Uh huh!”

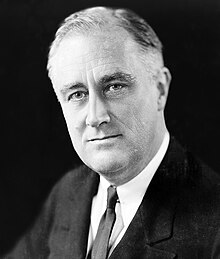

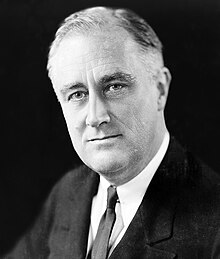

After a load of sweating and band music, we saw the sun bouncing and flashing off of the teeny spectacles of a genuine Used-to-be President of the United States, Harry S. Truman. He said it was great to be in a country where we could say mean things about the fellows in the government and not get thrown in jail, then go fight the whole world to defend our nation if we had to.

“That’s right,” said Dad under his breath. “I fought for this country and the right to gripe about those knuckleheads in Washington. I swear, President Kennedy’s the only fella in that town who’s got any sense.”

Between Dad’s commenting and the broiling sun over our heads, it was hard to concentrate on Mr. Truman’s speech. I thought about popsicles or would have if Clark hadn’t poked my arm. “Carmie, look at Jimmy. He’s getting sick or something.”

Sure enough, Jimmy was swaying. I grabbed his hand and called out, “Dad!” A lady behind us exclaimed, “He’s fainting!” all in the instant that Jimmy fell. Dad caught him and carried him through the crowd. Clark and I passed people squeezing themselves together to make a path for us. A sunburned woman wearing plaid shorts pulled a bottle of orange Nehi out of the cooler at her feet. “Here, hon. Give this to him.”

“Thanks, ma’am.”

President Truman, too far away to know about us, kept on with his speech.

Dad set him down in a puddle of shade under a tree by the parking lot. Soon puny-looking Jimmy was

drinking nice lady’s pop and Dad was fanning him with a newspaper.

“Golly, honey,” said Dad, “couldn’t you have waited until after the speech to go and faint like that?”

ker-BLAM!

“A cherry bomb!” someone yelled.

“Some darn kids blew up a trash can over there!”

I still had my hands over my ears when another BOOM came from the same direction: from the cars shimmering in the parking lot. Then there was a series of pop-BANGS , dog-barking, and people shouting, “Hey!”

“Some danged fool – !”

“...those tough kids – !”

“They tied firecrackers to that pup!” Dad hollered and a black, wild-eyed blur whizzed right past us. Zoom-away went Dad and Clark.

“Catch it!” Jimmy shouted, trotting after them.

I just stood next to the tree, both of us rooted to the spot and too smart to be running on a hot day. It was a long time before Clark and Dad came back.

“That dog’s probably in Kansas by now,” Dad said, wiping his red, sweaty face with the tail of his shirt.

“Where’s Jimmy?” I asked and in the next instant, we looked in the direction of scary sounds: tires squealing, people shouting and screaming.

Dad took a wild look around then glared at me. “I thought he was here with you keeping an eye on him!”

“Mister?” Some stranger hollered at Dad, “Is that your kid over there?”

We ran to where four or five sweaty people were bunching around Jimmy. Tears streaked his dirty face and his corduroys had a rip in them. He’d wrapped his bloody tee shirt around the dog.

“I think she – she’s dead!” Jimmy sobbed. “She was running because she was scared and a car hit her. The person who was driving didn’t mean to. I tried to save her, Dad.”

“Here now, boy,” said Daddy. “Here now. Of course you did. Let me look at her. Maybe she’s all right. Maybe she is. You come sit down, son.”

I could tell by the look on Dad’s face, as he examined the little dog, that it wasn’t all right, not at all. Folks clucked their tongues and shook their heads. Someone said, “That pup’s a goner. All’s you gotta do is look at it...” Then we heard a familiar, nasty voice: “Man! I ain’t never seen nothin’ so funny!”

The people around us turned to look and they parted so we could see Richie Scudder laughing out loud with his pimple-pussed buddies. “I never seen a dog run so fast: pop-pop-pop-pop! Did you get a load of that jelly-bellied kid scrambling to get a hold of that mutt?”

The creeps were too busy cracking themselves up to notice Dad bearing down on them. He grabbed Richie’s shirt with one hand and made a fist out of the other. He used the same voice he must have used on tough railroad cops in the bad old days.

“What’d you say?” Dad’s arm-muscle bulged out his angel-harp tattoo. “Did I hear you laughing at my boy?”

“Your boy?” Richie blurted while Dad kept right on, his voice getting louder and louder. “You kids tied gol-durned firecrackers to that pup? You kill a dog and laugh about it?”

“Kill it? We didn’t –! ” Richie looked over at us and anybody could tell he didn’t know until that minute what’d happened to the dog. Color drained out of his face down into his hightops. “Look, we was just havin’ some fun...”

“Pop him, Dad!” Clark cried. “Sock him in his snot-locker!”

“Take off!” Dad snapped. “Don’t let me catch you or your lousy friends messing with no harmless pups nor any kid of mine, you got that?”

Richie and his buddies walked away. One of them, when he was a safe distance from Dad, laughed, sort of. Dad snorted air out of his nose. “I should have punched that hoodlum,” he growled.

I saw a look on Jimmy’s face right then, a determined look that made me see how he would look and be when he became a grownup man. He ignored Clark telling him how brave he was. He just went off carrying that little dog in the direction of our car.

We were all quiet on the way home. Jimmy got to sit in the front seat. “I’m going to name her Cracker,” he said. “You think that’s a good name, Dad?"

“Yes, son. A fine name.”

He buried her in the backyard and helped Jimmy tamp Cracker’s scrap board of a grave marker into the ground. We all stood there while Jimmy read, in a steady voice, the Bible verses that began, “The Lord is my shepherd...”

I was glad for the dog that she had us to feel bad for her while she was on her way to heaven but still, her sad funeral made me all the more anxious for nightfall. At last it came, magic, buggy darkness full of pops, fireflies, and smoke. Georgie got to hold his first sparkler. From across the street, we saw the red spark of old Mr. Herman’s cigar along with its owner coming slowly towards us, to sit with us and watch Larry, Clark, and Harry running across the dark yard trailing smoky light like laughing comets.

Mama and Jimmy pushed the porch swing back and forth with their feet in a slow, comforting rhythm. Was the baby crying or dreaming in there, in Mama’s broad, firm middle? Planning what kind of person it was going to be? Was it hearing firecrackers all far away, like corn popping in the kitchen? Did it know what kind of family it had signed up for or were we all going to be its surprise too? Or did it still have a chance to be born to rich people in Paris? I wished I could talk to Robin about it. She said they’d be back right after the Fourth of July and anyway, she had to be back in time for my birthday next week.

A series of especially loud booms came from up the street. “Oh my goodness!” Mom exclaimed. She smiled down at herself and pressed her hands against her belly. “That woke up the baby.”

Old Mr. Herman ran his hand through the tuft of white hair on the top of his head and took his cigar out of his mouth. “I reckon that Skudder boy and his friends must’ve bought out the inventory at the fireworks tent out on the highway. Now you know,” he said, “he wasn’t always such a harum-scarum fellow. I can remember when Richard was a good boy, a proper lad, before he lost his mother.”

“Well,” said Dad, “he’s a proper knucklehead now.” With that, he walked over to where Mom was a nightcloud in the porch shadows. He bent down to kiss Jimmy’s cheek, then Mama’s belly and didn’t seem to mind at all that smiling Mr. Herman watched him do these things. Daddy handed Mom a sparkler, as if it were a rose and it lit up her mild, happy face. It was as if, sometimes, my folks were their own family, no matter how many kids came along to mess things up.

“Thirteen years ago, Carmenita, that was you in there,” Dad said, as he lit another sparkler and handed it to me. “Man, I was never so excited and nervous.”

Firecrackers popped, sparked, and danced in the smoky dimness as Mama stroked the top of Jimmy’s head. “It’s okay. Mama’s boy,” she murmured. Behind his glasses, Jimmy’s eyes were wide and dark.

I was more and more impatient all the next day and the next, waiting for Robin to come back. In the refrigerator was a strawberry cake Mom and I made to pay back Robin’s mom. In my sketchbook was a princess I drew to calm myself down. She was on top of her castle by an ocean. Wind blew her gown, her cape, and the silky veil flowing from the tip of her pointed hat. I was going to add a sailing ship for her to see in the distance, but I kept going out on the porch to watch for the Culpeppers’ big black car to come around the corner.

“Carmie, stay in or stay out! You’re making me a nervous wreck,” Mom said, fanning her bright face with a newspaper. “Take these kids up to the playground, why doncha?”

“But it’s gonna rain any minute.”

“I hope so! Maybe it’ll cool things off.” She lifted her chin to breathe in little breaths. “Go on now. I need to rest, just a little bit. Jimmy, you go too. You need some fresh air.”

Jimmy followed me and the little squirts out the door, looking like he’d a whole lot rather stay in and read his book.

The sky over the swings and jungle gym was an angel kingdom full of cloud-mountains, all dark and light, looking like a good place for thunder-gods and goddesses to have their palaces. I steadied Georgie on his twenty-seventh slide down the sliding board. The other boys were making themselves dizzy on the merry-go-round when we heard a huge thunder-boom.

Georgie screamed, half-scared, half-excited.

“Whoa!” Clark shouted. “Look at the lightning!”

“One-Mississippi, two-Mississippi,” Jimmy started counting.

“Come on!” I hollered. Big cold raindrops were already plopping on us and polka-dotting the playground. “You don’t have to know how close it is. Let’s go!” Thunder cracked like a giant whip. I scooped up Georgie and all us kids ran home through the rain, not even noticing that the Culpeppers’ big black car was back where it belonged. I didn’t even see Robin and her little brother on their front porch until she yelled at me.

“Boy oh boy, Carmen, if anybody ever says you Cathcarts don’t know enough to come in out of the rain, I’ll tell that person he’s full of prunes!”

Over on the Culpeppers’ front porch glider, our stories, Robin’s and mine, tumbled out and collided into each other.

“Mr. Herman told Jimmy he saw Mrs. Truman up at the store…Hey, did you know Richie’s got a job there?”

I left out Clark embarrassing me with his big mouth and me seeing that cute boy. “Anyway, she was buying a can of pork and beans and...”

“...fireworks in St. Paul and my dad played the piano in a wedding for one of his cousins. I got a new dress for it and ...”

“...that poor little dog! You shoulda seen the look on Richie’s face when he thought my dad was gonna sock him – hey, the rain stopped!”

“We had to stop the car right by this busy road so Darren could puke from eating seven hot dogs in a row and you shoulda seen my mom...”

“Hey, my birthday’s next Friday. Did I tell you that?”

“Nope. Mine’s October 27th. I wish I’d waited and gotten born on Halloween.” Robin shrugged her shoulders. “So are you going to have a party?”

“Not really.” My whole insides were buzzing with the good news I’d been saving up and putting off telling, to make it even more exciting. “We’re gonna have my cake on Saturday because Dad works Friday, right? He works nights now, but so anyway, listen: My aunt – you’re really going to like her. She’s going to take off work so she can take us, me and you, to the movies over in Kansas City and go see Cleopatra! Won’t that be so neat?”

“I’m not sure that would be an appropriate film for Robin.”

“Mom!” Robin jumped to her feet; we both did. Did I even notice Robin’s mom in her doorway listening to me? No.

“No, please!” I said. “My Aunt Bevy’s gonna call you and…”

But Mrs. Culpepper had turned her attention to Jimmy who was carrying a pink-iced cake across the driveway into her yard. “Is that for us? How nice!”

Then she caught sight of her kid over in our yard full of puddles and boys. Immediately her smiling mouth was a scowl. Words began pouring out of it like BBs out of a bucket. “Darren Albert Culpepper, you’re soaking wet! And filthy dirty! You come get cleaned up! Robin, we’ll discuss this later. Thank you; what did you say your name was? James? Did you help your mother make this cake?

Oh, you did, Carmen? Well, how very nice; you and your brother had better run along now. Robin needs to set the table for supper. Darren, leave those disgusting sneakers on the porch. We’ll see you later...”

Robin signalled me with a quick look at her treehouse. Her lips made the word, midnight as all three Culpeppers went inside and their door clicked shut.

Four

In which I climb a tree; I get a penpal and a friend.

We Cathcarts go to the store.

Mrs. Culpepper’s mouth opened and her eyebrows shot up to her teeny bangs. “I beg your pardon?”

“Uh, my…er… I mean, no thank you, ma’am. That’s real nice about the cake,” I babbled my way out the door. “But, well – we’re allergic! And I gotta go home now. Nice to meet you guys – honest!”

Outside, goony Darren and Clark were yelling, “So long!” to each other and “Hi!” to Dad as our old Rambler surged up the driveway. Harry and Larry exploded out the front door. “Daddy’s home!” Dad’s eyes and big grin looked light in his grimy face. He wiped his hand on his work pants and handed me his lunchbox so he could hug my shoulder. “Hey, Buddy. How’s your mom?”

“She’s fine.” Especially now, I thought, since I’d saved her from what we both hated: unexpected, snooty company. “Did your job go okay?”

“Well, if you don’t mind getting bossed around, being on your feet all day, lugging loads, and turning screws, it was alright. Beats looking for a job!” He stopped paying attention to me so he could pick up the twins. They clung on to him, like baby monkeys, as Dad then Clark and me followed up the porch steps, Dad hollering, “DOR-thy!”

Next door, Robin was making a silly face at me and twirling her finger at the side of her head. I frowned back at her. Did she mean me or her cranky mom? I went on inside.

Robin probably meant I was the nutty one, saying we were allergic to cake and running off like that. But then I looked around and saw what Mrs. Culpepper would have seen, through her icecube eyes.

We’d only been here one day and already George had scribbled on the walls. Toy trucks, squashed gobs of clay, TinkerToys, and blocks covered the floor. I saw baskets of clothes waiting to get folded, cereal bowls, and chocolate milk glasses perched on stacks of Mama’s beloved magazines. I saw a roach speeding home to the wife and kids living in a 1957 Ladies’ Home Journal. The little boys had crowded back around the television, their faces six inches from the black-and-white blast of Three Stooges reruns. Jimmy was flopped on our squashy couch with the poking-out springs and falling-out stuffing. He was eating a sandwich and reading about Kit Carson, using my art book for a lap desk. I sniffed at peanut butter, grubby boys and – something else.

As soon as I got my art book stowed under my pillow upstairs, I clumped back down to find Georgie. “Come on, kid,” I said. “Let’s go find you some dry pants, okay?”

He smiled up at me. “Okay, Carmie.”

“You gonna remember to go potty like a big boy next time?”

His smile dimmed. “Okay.”

Robin would be cuckoo too, if she was always having to get some little squirt to use the bathroom like

regular people.

I peeled wet training pants down Georgie’s rubbery legs as he held tight to my shoulders and I imagined me perfecting this and everybody in it. Digging around for a little pair of dry pants, I decided that I’d definitely not be cheerful. There’d be no whistling while I worked, like Snow White in the cartoon. No, I’d be a goddess, a fierce one, who needed no bunnies or birdies to help her. I saw, like in a mind-movie, my white robes, my long red hair flowing and blowing against the blackest of thunderclouds, and sparks shooting out of my keen (no glasses) mythological eyes. With a well-aimed lightning bolt, CLEAN was our house! OUT went the television reception right in the middle of the boys’ cartoons – ZAP! Into a giant trash can went all our junk: Everything but the encyclopedia and whatever was mine. Flames licked the clouds!

In real life, Daddy was smooching Mama, all blushes and giggles. He even kissed her butter yellow dress where it was stretched over her belly and the baby inside. I felt my own face get hot.

I survived all of the usual suppertime burps, farts, spills, sit-up-straights, clean-your-plate’s and don’t-play-with-your-food’s, only to see Darren Culpepper’s face mashed into the front door screen. “Clark! You in there? Come get this cake, wouldja? My mom made it for you guys. Then can you come out and play?”

Robin was out there too. I hurried out to the porch, telling her, “It’s so nice and cool out here. You wanna sit on the swing?”

She did, but she stole glances through the window, trying to see what was so mysterious in our house that I wasn’t asking her to come in like any regular person with nice manners would do. Robin was probably wondering exactly what kind of a goon I was. “How come you didn’t want us to come over? And you were fibbing, right? About cake making you guys sick?”

“Well, uhm, we aren’t really settled yet and, you know, company makes my mom nervous…” My voice trailed off with her looking at me like lawyers on TV looked at criminals in the witness chair.

“Okay, okay,” I said. “I just didn’t want you all to find out that we’re a messy bunch of nuts.

“You did seem pretty crazy. Of course, I like that in a person. My mom just said that she wished I was allergic to cake so I wouldn’t be so fat.”

“She did?”

Instead of answering, Robin pointed at the tree in her yard. “You wanna come and see my office?”

“Sure.” I really did, too, but I got scared as soon as she was up there and I was still on the safe, hard ground. She called down through the leaves, “Come on! You’re not a scaredy-cat, are you?”

I was. I was a nut and a scaredy-cat.

I struggled up the rope ladder until Robin helped me onto the floor boards that had been wedged into three big branches. The leafy roof made deep shadows so she shone her flashlight on an old sofa cushion and a wooden box with a lid and a lock. “To keep Darren and the other squirrels out,” Robin said with a grin. It was stocked with a half-eaten bag of potato chips, pencils, a notebook, some jacks, acorns, a spare yo-yo, two candy bars, and a package of pink Hostess Snowballs. She ripped these open, handed me one and took one for herself. I fished a Trixie Belden mystery out of the box. “You read these too?”

“Yeah, Nancy Drew, Sue Barton, Betsy-Tacy, Laura and Mary on the Prairie. I like all those books.”

“Me too.”

“This is the best part of my whole life,” Robin said. She popped half a Snowball into her mouth all at once. She ate the other half, licked her fingers, flicked a cake crumb down at her house, and said, “Mom doesn’t allow me to eat junk like this.”

We swatted at mosquitoes and dangled our legs off the edge of the treehouse in the blue-green twilight. It smelled like summer. I could see Mama moving about in the yellow light of our kitchen. It was quiet around us except for birds and cricket until we both heard Mrs. Culpepper’s voice coming from inside her house. “She sounds kind of mad,“ I said, and hoped that wasn’t rude.

Robin snorted. “Old Yeller. That’s my mom’s nickname and she doesn’t even know it.”

I put a hand over my smile.

“She’s okay, really,” said Robin. “She likes every-thing just so and wishes I weren’t such a big fat tomboy and was cute and precious like Darren instead. My dad doesn’t yell at us. He’s nice. Tell me about your folks.”

I hesitated. “It’s not a pop quiz, you know,“ Robin said,

“Well, my mom’s pretty quiet and my dad’s nice too, except for when he gets mad. He blew his top the other night and smacked me.”

“Huh?”

I felt guilty, tattling on my basically-good dad, but I did it anyway. “He did. Right in front of half the town over at Mugs Up.”

“He did not!”

“Did.”

“Why?” Like I must’ve done something terrible.

“I shot my mouth off about Mom having another baby.”

“Don’t you like being in a big family?”

If I said no, I’d be a traitor plus it wouldn’t be exactly true. And it’d sound too dumb to say I’d rather be an artist than a big sister. After a long moment of me not knowing what to say, Robin handed me a Milky Way and punched me in the arm, friendly-like. A girl never did that before and it gave me a nice feeling. I punched her arm too and unwrapped the candy.

“I wish you guys didn’t have to go to Minnesota.” I wished we could just stay up in the tree forever, but no. We jumped at the sound of Mrs. Culpepper saying,

“You and Carmen had better come on down out of there. It’s late.”

“In a minute,” Robin called down.

“Now!” her mom barked. “I’ve got your bathwater running.” She disappeared with a soft thwack of the screen door.

It was late, late, late before I fell asleep. The pictures in the Botticelli book from the library were too beautiful to stop looking at. I ran my fingers over the perfect faces Mr. Botticelli painted in Italy in the 1400s. Was that how Italian ladies looked? If I really practiced could I draw and paint like that? Be a great American artist in the 1900s? The thought made a buzzing by my heart.

The book was beside me in my bed when I woke

up. I looked out the window and saw that the Culpeppers’ shiny black Buick was gone. It was off somewhere, carrying them north to Minnesota.

Clark yelled at me from way downstairs. “Car-mie! Robin left a note for you! Under the front door! Want me to read it to you?”

“NO!” I scrambled into my shorts. I ran downstairs while Clark bellowed, “’Dear Carmen, I’m real glad you guys moved next door...’”

“Stop it, you little brat!”

“’We could be penpals if you want,’” he went right on. “’Here’s my grandma’s address....’”

I grabbed the letter away from my dopey brother. He laughed then a light bulb must’ve lit up in his pointy little head. “So then could I write to Darren?”

“If you can write,” I muttered, reading over the note for myself. I smiled: Robin Culpepper wanted us to write to each other.

“As good as you,” he told me and stuck out his tongue. It had crumbs on it plus there was chocolate frosting all around his mouth from having Mrs. Culpepper’s cake for breakfast. We all did and saved the last slice for Dad.

“Robin’s mom is kind of cranky,” I said to Mom, “but she sure makes good cake.”

“We’ll write her a thank you note.”

“I’ve got the address. Robin and me are penpals.”

When I wrote to her, I tried to make babysitting little brothers, hanging laundry on the clothesline, and making Kool-Ade sound super-interesting. I didn’t tell her about the best part of my life: staring at the Botticelli pictures and trying to draw my favorites, in case she might think I was a goon. And I was too shy and too chicken to tell Robin I missed her, but she was brave. On the back of a fish postcard she wrote:

Dear Carmen,

My grandpa took me to this lake. I caught a walleye. To see what it looks like, turn this card over. Are you guys getting settled? Tell Jimmy I say hello. Yours ‘til the ocean wears rubber pants to keep its bottom dry.

Your friend,

Robin Delaine Culpepper

P. S. I miss talking with you.”

I couldn’t help smiling with happiness, then I chewed my lower lip. Robin hadn’t ever been inside our house. Would she really want to be my friend if she ever saw how messy we are and that we NEVER get settled? She might think we’re lazy instead of folks who can’t ever seem to get organized. We never found enough places to put stuff away and no matter how junky, our old clothes and magazines were, according to Mama, “too good to throw away.” We piled it all in corners and shoved it under beds.

“I’ll sort through it all one of these days,” Mom said, settling herself on the couch in front of the fan. “Georgie, come take a nap with Mama.”

“No.”

Almost two weeks after we moved in, I found our guardian angel picture in a paper sack and put it up in the front room. It’d hung on the wall at Blue Top and every other place we’d lived. The angel wasn’t as beautiful as Mr. Botticelli would have painted her, but she was pretty. A hundred times I’d tried drawing her floaty hair and soft face. She was always on duty, keeping a pair of pink-cheeked little knuckleheads from falling into a bright blue river. How did angels get their robes off over their wings, I wondered. And did they ever get bored, sick, and tired of having to watch over people? I asked Mama, “Do you think we really have a guardian angel?”

She opened her eyes and looked at the ceiling, as if our angel might be gazing back at her through the cloudy water stains. “Oh,” she said, in her soft, vague-sounding voice. “I’m pretty sure we do.”

On a postcard with a picture of a wagon train on it, I wrote to Robin about it.

Saturday, June 14, 1963

Dear Robin,

Do you believe in guardian angels? I think I do. I saw the baby kick from inside my mom. Her belly feels like a basketball. It’s kind of creepy imagining that somebody’s INSIDE of there, thinking about stuff. What if THIS baby is twins, like another Harry and Larry? Scary! It’s boring here without you next door. I miss you too.

When you’re old and you have twins (I hope you won’t!)

Don’t come to me for safety pins,

Mama walked by me as I was writing Your Friend, Carmen.

“Carmie, don’t let me forget my pickles and sardines when Daddy takes us to the store later.”

I grimaced at (1) the treats Mama loved to eat when she was going to have a baby, and (2) the idea of us Cathcarts going to the store together.

“Oh, the kids and I will go in for you, Dee,” Daddy said, later that evening. “You rest yourself out here in the car. Just give me your list, why doncha?”

“No, now, I’m fine,” Mama told him. “I like to pick things out.”

Would it even do any good to ask to stay in the stationwagon by myself and draw? Or try, in the store, to keep my distance from my slow-moving mom and the rest of my family? Nope.

Dad grabbed a cart and patted Mama’s arm. “Carmie and I will keep the boys out of your hair.”

Looking after little kids mostly boils down to following them around, trying to keep them from getting broken while they’re breaking everything else or sliding down the slick floors between rows of canned goods. That’s where Harry dropped a can of peaches in heavy syrup on his foot, then Dad gave Larry a spanking for horsing around and busting a box of eggs.

Both twins were bawling when a woman on the loud speaker barked, “Clean up in Aisle 8.” I was keeping my eyes down or I would have noticed that the kid with the paper hat and the mop was none other than creepy Richie Scudder. “Oh man, I might’ve known,” he said, real loud, so people would know how disgusting and messy us Cathcarts were. An annoyed-looking woman and the cutest boy I ever saw turned to stare at us. And wouldn’t you know they were right next to us later on, over in Aisle 3: Paper Products and Hygiene Items, where Clark was practicing his reading. “Carmen,” he hollered. “What the heck are ‘Sa-ni-tar-y Napkins’?”

The cute, sandy-haired boy made a face and his mom rolled her eyes like we were the world’s worst, low-class weirdos.

Could there BE anything more embarrassing?

“Carmie,” Dad called to me as I fled the scene, “you’re as red as a tomato! There’s nothing to be shy

about!” Which made the whole thing even more hideous.

Before we got out of there, Georgie had another tantrum. The plump checkout girl flat refused to ask Clark “Who’s there?” no matter how many times he said “knock-knock.” When I grow up and I am a rich, famous artist and embarrassing relatives come knocking on my studio door, I’ll be just like that girl. I’ll ignore them and hope they’ll go away.

Mama collapsed into her seat while Dad and Jimmy and I loaded all the grocery sacks into the back of the station wagon. Mama fanned her red face and told us all to be quiet because she felt like all the air was out of her tires.

“Yeah,” said Dad, “Everybody just put a sock in it back there.”

I didn’t say a word, not even when we were almost home and I remembered that we all forgot Mom’s sardines and her sweet pickles.

“Oh well,” she said later on. “We’ll pick them up on the way back from my appointment on Friday. Daddy’s taking off work to get me to the doctor and Carmen, you and Jimmy can look after the little ones.”

“Will you tell them they have to mind us?”

Harry and Larry made faces at me and stuck out identical tongues. Mom gave all the boys her sternest look and said, “Everyone just be nice.”

That was what she always said about the whole world, the Communists over in Russia, Fidel Castro in Cuba, Jews and Arabs in the Middle East, black and white people in America. That goes for everybody: just be nice, for crying out loud.

Jimmy, off at the library, taking our books back, got out of babysitting. Not me. I showed Clark and the twins how to make a brontosaurus out of clay. “Look, you guys, you stick your little fingernail in its face. That makes a smile.”

“Make a tyrannosaurus rex!” cried Larry.

“Then he can eat these guys!” Harry growled.

They both roared and bared their teeth as they made their dinosaurs extinct between the palms of their hands and watched cartoons. Georgie’s thumb slipped from its mouth socket as he fell asleep on the floor beside all the toys, coloring books, broken crayons, and mashed reptiles.

“Clark, help me pick this stuff up, wouldja?”

“You’re not my boss.”

He wouldn’t quit watching Popeye and Bluto even one second so I thumped his head – not hard. I’d’ve tidied up the whole room, but the mailman brought a new magazine with Mrs. Kennedy on the cover. Inside were more pictures of the First Family plus news that they were going to have another baby too. Maybe it’d have the same birthday as our baby. Maybe they’d invite us to the White House, I thought, as I studied an especially nice picture of Jacqueline Kennedy. Next thing I knew, I was drawing her face on a piece of notebook paper. Drawing’s just daydreaming with a pencil. That’s all I was doing when I suddenly got yanked back into my real world. Where was our blockheaded guardian angel when Larry decided to skip his way downstairs? The little dope didn’t bust any bones or even bleed, but did that keep him from howling all the louder when he saw that Mom and Dad were home?

“Was everybody nice?” Mama asked.

No, but I was the only one who got yelled at.

To any who might be reading this, bless you, thank you, and I've added hyperlinks, highlighting the historical context hoohah. So you can see what some of the real-life people & places look like. CH

JFYTK/Chap. 3

In which us Cathcarts and the neighbors meet each other,

Jimmy and I go to the library, and I help Mama get out of having company.

It was still dark early morning when Dad put his freshly shaved and Aqua Velva’d face close to mine and asked, “Are we still buddies?”

“Sure.”

“You make sure you get along with your mama today, okay?” I felt a kiss and his warm peppermint breath on my cheek. “She’s gonna need your help this summer. No spending all your time with your nose in a book or drawing pictures. You’re a big girl now.”

“Okay,” I told him. Okay, okay, just go away. Then, to make up for thinking that, I wished him good luck on his new job. He wasn’t a mean dad, not really.

I found Mama in the basement, stuffing jeans into her washing machine. We didn’t have one at Blue Top.

There she had to wait until Daddy could drive her to the

Washeteria in Osceola. She pointed at a couple of big laundry baskets “The best way to help me,” she said, “would be to go hang all this on the line out back. How ‘bout that?”

“Okay.” I couldn’t help noticing that she sort of leaned against the washer, as if she was too pooped to stand on her own. “But don’t you wanna go up and lay down or something?”

“It’s nice and cool down here. I’ll be up in a minute and later,” she said, “maybe you and Jimmy might want to take a walk? See the neighborhood? Not too far, you understand, but maybe you could get acquainted with the library up by the courthouse? I think it’s on Liberty Street. We don’t have to get all settled right today, do we?”

“Nope,” I said. “We could put it off a day or two.” I returned her smile, then I about killed myself, lugging first one heavy basket of wet clothes, then another up the steps and out the back door. I got a look at our new old house in the daytime. It looked better at night, I decided, and pretty ratty compared to all the other houses on our street.

As I pinned up two or three hundred underpants and things, Clark and the twins played Hide & Seek between the wet workpants and bedsheets with a goofy-looking kid with a blond flattop. “This is Darren Culpepper from next door,” said Clark. “This is Carmen. She’s the oldest.”

The little squirt didn’t seem to know what to say to that. He just wiped his nose with the back of his hand and squinted up at me so I asked him, “You any relation to somebody called Robin?”

“She’s my big sister.”

“You guys got a tree house in your front yard?”

The kid frowned. “Yeah, but Robin hardly ever lets me play in it.”

As soon as Jimmy and I started out on our walk, the old man across the street waved at us and began shuffling across his tidy yard. “Hello there!”

The old fellow offered us the hand he wasn’t using on his cane. We shook it and smiled back at him. “Let me tell you children welcome to the neighborhood,” he said.

“I’m Oscar Herman. Isn’t that a terrible name: Oscar?”

“I kind of like it,” Jimmy said.

“Me too,” I added, and it was true. I did.

“She’s Carmen Cathcart and I’m Jimmy. I’m her brother.”

“Why, those are nice names!” said Mr. Herman with a grin. His teeth looked very white and storebought. “Happy to know you.“ Now he used his free hand to tip his ball cap at us. He pointed his walking stick up the street to where two straw-hatted black ladies were bent over working in a garden full of zinnias.

“They’d be the Monroe sisters.” Mr. Herman cranked his voice up louder, “Hey there, Miss Lillian. Pretty day, Miss Effie!”

They waved and called out, “Mornin’, Oscar.”

“These here’re your new neighbors, Carmen and Jimmy!” He paused a little bit and hollered, “Cathcart!” We all waved and said ‘hey’ to each other

Mr. Herman said to us, softly now, “Miss Effie’s the skinny one and the fat one’s Miss Lillian. They both got the arthur-itis -- so do I! -- but they sure do keep up their flowers.”

“Sir,” I told him, “we gotta go to the library. Can we bring you a book?”

His furry eyebrows rose up at the suggestion. “No thanks, I got forty chapters to go on the one I’m reading.” He told us how to find the library as he reached into his pants pocket for a couple of thick white peppermints. “You and Jimmy take these now.”

We thanked him and headed up the sidewalk. It was shaded by trees, broken and humped in places from their roots, like toes poking up under the blankets. Jimmy’s tee shirt was stretched over his soft middle and tucked into his corduroys. I had on my cutoffs. They showed off my knobby white legs to anyone who might be watching. Up by the house on the corner, someone was. “Hey, Jelly-Belly! Who’s your bird-legged girlfriend?” A high school kid sneered and blew a puff of cigarette smoke at us. He was leaning on the propped-open hood of big car, the kind Dad called a “road barge.” It sat next to a rusty-looking pickup truck. “You part of that hillbilly family that moved into the spook house?”

He looked like he’d put the black oil from his old Cadillac right on his hair. Just as this bozo flicked his cigarette at us, a flying something out of nowhere bopped him on the head. “Ow!” he yelped.

There she was, the moon-faced, tree girl, standing in the middle of the sidewalk with her hands on her hips. “That’s what you get, Richie Scudder, you creep!”

“Yeah, yeah, big talk, Pudge,” he jeered back. He picked up the apple she’d thrown at him and took a bite out of it. “I was just welcoming the little twerps to the neighborhood.”

The girl spit on the sidewalk in his direction, then walked over to us. “Richie thinks being a bully makes up for being a dope.”

She was pretty. Her eyes were the kind with smoke rings around the blue and her skin was pale like Snow White who’d have gotten terrible sunburns if she hadn’t lived with dwarves in the woods where it was shady. I admired the red ribbon braided through her long black pigtails and couldn’t help grinning at her.

“You’re Robin Culpepper, right?”

At first she frowned, me knowing her name and all. “So who are you?”

“Carmen Cathcart.”

Jimmy poked his hand out at her the way Mr. Herman had to us. “And I’m James.”

James!

Robin smiled and shook his hand.

“You want to come with us?” he asked. “We’re going to get our library cards.”

She tilted her head sideways, sizing us up. “I gotta go ask.”

At first I was afraid she’d be sorry she went to all the trouble of getting her folks to let her go for a walk with us because Jimmy was in an informative mood. He told her all the other kids’ names, that we’d lived on a farm, that we used to have a goat named Gertie, and that goats’ eyes are shaped like rectangles.

“Not the whole eye, but the black pupil thing in the middle. Our eyes and turtle eyes are round -- cats’ are pointy. That’s just for you to know. And guess what else?” he said before I could shut him up. “Our Mom’s gonna have another baby!”

“Neato! A brand new baby -- right next door! It must be fun, being in a big family,” Robin said, digging a yo-yo out of her shorts pocket. “Ours is just my folks and Darren and me.”

Fun? The words ‘hillbilly family’ were still scorched and smoking in my brain, I glanced at Jimmy and said, “It’s sort of fun. Sometimes.” Okay, it was. Sometimes.

Richie came roaring past us, blasting his car horn. “Creep!” we called after him. “It’s a good thing you guys moved into that house,” Robin said, sending her yo-yo out and back, snap. “I was afraid it was gonna be buried in weeds and junk like a Sleeping Beauty castle with the ghost of old lady Millinder -- that used to be her house, you know -- still spooking around in there. Or it’d get torn down like my mom says it should’ve been years ago --.” Robin flicked a wary look at us. “Sorry. I shouldn’t have talked about your house like that.”

Since I didn’t want to say I agreed with her mom, I changed the subject. “So is your junior high school really big?”

Robin yo-yo’d a few steps before she said, “Yeah. When I first went there last year, in seventh grade, I got lost a lot. You gotta be quick between classes, getting to your locker and stuff.”

Oh brother.

“We’ll walk by Maple Street,” she went on, “so you can see it if you want to.”

“I do,” said Jimmy.

The school was made out of bricks. It looked old-fashioned -- and huge, compared to the school we’d been going to. Jimmy and I stared at it while Robin Rocked-the-Baby with her yo-yo. I think she figured out I was nervous.

“’Everybody’s dumb the first week’ is what my dad says and he teaches high school.” Then Robin kind of bugged out her eyes. “This whole junior high thing gives me the creeps. Don’t tell anyone, but I still miss elementary.”

“Me too,” I said, feeling relieved. Maybe eighth grade wouldn’t be too gross after all. To make myself seem like a casual person someone would want to be friends with, I picked up a stick and clattered it along a picket fence as we went on walking. “Have you always lived in this town?”

Robin nodded. “Same old house, same old town. Boring, huh?”

“I think that’d be neat,” I said softly.

“Me too,” said Jimmy.

“Hey,” Robin said, “if you guys are new, maybe you don’t know that big white house over there is where President Truman lives, him and his wife.”

“He’s the one who decided to drop the big bombs on Japan,” Jimmy told us even though we knew that already, of course. “Dad said it settled their hash once and for all and ended World War II, but still --. Do you guys suppose he has nightmares? About those bombs?”

Robin didn’t think so, but she didn’t look too sure about it. “Do you like President Kennedy?” I asked, following after her.

“My dad and I do. My mom voted for Mr. Nixon, though.”

I liked our president. I’d tried to draw him and the First Lady a thousand times, but I never yet made them look as handsome and beautiful as they did in Mama’s magazines.

We walked past a statue of Andrew Jackson on a prancing horse on a big stone pedestal. Robin gave Jimmy a poke in the arm. “They named this county here after him. Just for you to know.”

Jimmy gazed up at the statue. “He was the seventh president,” he said, kind of automatic and dreamy. Robin’s eyebrows went up, like she’d never met anybody like Jimmy.

In the dim, cool library, Robin aimed us at a lady who gave Jimmy and me library card forms to fill out. “You can each check out one book today,” she said, “since this is your first visit.”

“Do you have any art books?” I asked.

It turned out that she had loads of big, thick, glossy ones. Robin and Jimmy went off to the kid books while I followed the librarian’s pointed finger to the art section. “Boy,” I whispered, “I’m going to love living here!”

I pulled a heavy book out of a bottom shelf. The outside said BOTTICELLI. That was the painter’s name, it turned out. The book was full of pictures of what must have been his painted daydreams of a mythological country full of pale, purely beautiful goddesses with long necks like flower stems. Just the sort of fairytale perfection you’d never find in real life. Not in mine anyway.

“You gonna carry that book all the way home?” Robin asked. “It must weigh four or five tons.”

“It’s okay.” I cradled the book in my arms, which were about to fall off by the time we got to the grade school on the corner by our street.

“That school’s about three times bigger than the school we went to in Vista,” said Jimmy.

“My mom teaches first grade there,” said Robin. “Hey, maybe she’ll have your little brothers in her class.”

I rolled my eyes. “Lucky her.”

Robin glanced at her house. “You guys wanna come in?”

“Uh, no thanks.” Jimmy held up his biography of Kit Carson from the library. “I gotta go read my book.”

“I do,” I told him, “so could you take my book with you?”

“Sure, okay.” Jimmy took my Botticelli book, then made a face like I’d handed him a sack of cannonballs.

Robin’s house smelled like Clorox, Ajax, furniture polish, floor wax, and cake-in-the-oven. I marveled at the tidy, polished, rich-people living room. There was even a glossy black piano with its lid up, like on television. I saw a bit of gleaming kitchen.

“My folks must be in the back yard or something,” said Robin. “Wanna come see my room?”

“Sure!” All along the carpet-covered stairway, pictures of Darren and Robin, from baby-days to now, marched up the walls. At the top of the stairs there were suitcases.

“We’re going up to Minnesota to visit my grandparents,” Robin said, seeing my curiosity. “We go every year.”

We just met and she was leaving? That was a lousy thing to find out. “When will you be back?”

“After the Fourth of July,” she said. “This is my room.”

It was like walking into a magazine picture of “A Perfect Blue and White Bedroom For Your Little Girl.” There was a dollhouse in the corner and a canopy over Robin’s bed. It made me feel kind of rotten and jealous.

“Where have you been?”

A tall woman with short dark hair and a starched blouse was standing in the doorway. It looked like you could slice boiled potatoes with the sharp crease in her slacks.

“We went to the library, Mom. Dad said I could go.” “Well then, you can tell him why you’re late for your piano lesson. Did you go downtown with your blouse not even ironed?” Then she looked at me and flicked the smile-switch in her head to ON. “I’m Mrs. Culpepper, Robin’s mother. And you’re --?”

“Carmen Cathcart” I said. “Uh – we just moved here yesterday. You know, next door.” I motioned my hand in the direction of my house while Robin tried to iron her plaid blouse with her fingers.

“Well, Carmen,” Mrs. Culpepper said, as we followed her down the steps past all the pictures, “your mother must have her hands full, getting settled and all. And is it true what my son tells me? That she’s going to have another little one soon?”

“Yes, ma’am.” My face felt like one of those cartoon thermometers going hotter, hotter, up, up, up.

Aunt Bevy said once, “For every person you meet there’s a wonderful-horrible set of stories that would just flat wear you out if you knew ’em.” Just by going in her house and meeting her mom, I got a lot of clues about Robin. I figured Mrs. Culpepper probably deserved to have Harry and Larry in her class.

“Is this the girl-next-door?” said a deep voice. The light haired, cheerful guy who owned it gave Robin’s braid a friendly tug. “Jim Culpepper,” he said, sticking out his hand for a shake.

“I’m Carmen, uh, Carmen Cathcart. Nice to meet you.”

Robin’s mom went off to her shiny kitchen. Mr. Culpepper plunked himself down at the piano and began playing as good as on a record. He asked me if I liked Beethoven and I remembered that he was a high school music teacher.

“Uh, yes sir. I think so.”

“Caaaaaar-men!” Clark hollered from out in the yard, “Mama wants you!” just as Robin’s mom appeared beside me, a cake in her hands.

“We’ll walk over with you, Carmen, and welcome your mother to the neighborhood -- Jim?” She’d have snapped her fingers at him, seemed like, if she hadn’t had her hands full. I looked from Robin to her parents. Good grief! These tidy people? In our crummy old messy house?

“No!” I blurted.