Thursday, February 23, 2012

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Couple o' Dames/Couple o' Thoughts

So, having rec'd a red-bound birthday book from my author friend Vicki 'Greatheart' Grove, and because I'm the sort of history buff-shut in who does this sort of thing, I've since made something of a daily ritual of looking up today's birthdays then tracking down something interesting he or she said [and write down the good ones in another little book - feel free to roll your eyes, but oh well, it gives me pleasure and that's something in this mean old world, no?] and I'm glad I do because I come across the most interesting people, such as these two dames, both of whom I want to read more of now.

So, having rec'd a red-bound birthday book from my author friend Vicki 'Greatheart' Grove, and because I'm the sort of history buff-shut in who does this sort of thing, I've since made something of a daily ritual of looking up today's birthdays then tracking down something interesting he or she said [and write down the good ones in another little book - feel free to roll your eyes, but oh well, it gives me pleasure and that's something in this mean old world, no?] and I'm glad I do because I come across the most interesting people, such as these two dames, both of whom I want to read more of now.

"There is only one importance & it is the history of what you once believed in & the history of what you came to believe in." Kay Boyle 1902 ~ 1992

Saturday, February 18, 2012

deathday

"...in his mind's eye, St. Peter's...he entered the church through its front portal, walked in the strong Roman sunshine down the wide nave, stood below the center of the dome, just over the tomb of St. Peter. He felt his soul leave his body, rise upward into the dome, become part of it: part of space, of time, of heaven, and of God."

"...in his mind's eye, St. Peter's...he entered the church through its front portal, walked in the strong Roman sunshine down the wide nave, stood below the center of the dome, just over the tomb of St. Peter. He felt his soul leave his body, rise upward into the dome, become part of it: part of space, of time, of heaven, and of God." Thursday, February 16, 2012

NEW BOOK! WAHOOBAYBEE!

A book that I illustrated, once Julie Cummins had written it, that is, is OUT. Today is the pub date for Women Explorers from Dial. It's a follow-up to our Women Daredevils. There is a brief essay for each of 10-or-so women, each one of which is far and away more adventurous and brave than I. Can't speak for Julie...

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Valentine

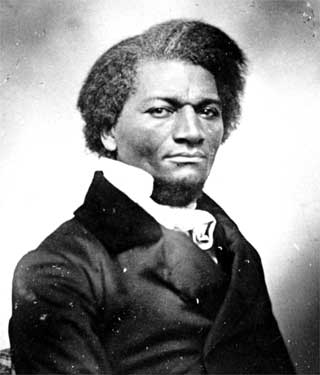

"Find out what any people will quietly submit to & you have the exact measure of the injustice & wrong which will be imposed on them."

"Find out what any people will quietly submit to & you have the exact measure of the injustice & wrong which will be imposed on them."So, I didn't send any valentines. I meant to [but I've been too obsessed w/ current enthusiasm: my illustrated Missouri History - I want to have it done by spring] & I felt especially badly, having happily rec'd a few. Frankly, not wishing to wish the days of my life away, I'll still be glad to see this holiday over with. Pretty sick & tired I am of all these sappy commercials. Ah well. Still I might well have sent one to this guy. What a heroic and remarkable gentleman Mr. Douglass was. I hope he knows that he's still remembered & honored. He's well more than some Black History Month icon. Frederick Douglass and his example ought to be remembered every day of the year. God rest him.

Monday, February 13, 2012

Bess

Oh I so should have posted something yesterday. Birthday-wise, you can't do much better than the 12th of February. Lincoln. Darwin. Gen. Omar Bradley. One of my favorite authors, R. F. Delderfield, whose 100th birthday anniversary was yesterday. If you're reading this, track down his A Horseman Riding By, the first of a handsome trilogy called - isn't this a lovely title: Long Summer Day. So is the setting, an estate in southern England, in the first four decades of the 20th century. One of those generational sagas. Very Masterpiece Theatre, to which I'm addicted these days, thanks to the denizens of Downton.

Oh I so should have posted something yesterday. Birthday-wise, you can't do much better than the 12th of February. Lincoln. Darwin. Gen. Omar Bradley. One of my favorite authors, R. F. Delderfield, whose 100th birthday anniversary was yesterday. If you're reading this, track down his A Horseman Riding By, the first of a handsome trilogy called - isn't this a lovely title: Long Summer Day. So is the setting, an estate in southern England, in the first four decades of the 20th century. One of those generational sagas. Very Masterpiece Theatre, to which I'm addicted these days, thanks to the denizens of Downton. Just For You to Know: Chapter SEVEN

Chapter Seven

In which I become thirteen, I imagine Egypt,

I learn about America and the real world.

I sat between Robin and Aunt Bevy in an old Kansas City movie palace, our faces turned up to the big screen, watching the magnificently eye-shadowed Queen of the Nile. Only a few hours earlier I’d been sitting beside Mama, watching this same actress, Elizabeth Taylor, pretending to be (National) Velvet Brown, back when she was probably my age and not allowed to wear all that makeup.

I covered my third yawn with my hand. “Don’t you like the movie?” Aunt Bevy whispered into my ear, “You’re not bored are you?”

“No! I love it! I didn’t sleep much last night, that’s all.”

Her lips twitched. She pointed at the person on her

other side. Jimmy, who’d won a hard campaign to come with us, was sound asleep.

Cleopatra was the best grownup movie I ever saw and we got to see it on the best day I’d ever lived, so far. Jimmy and I hardly ever got to go to the movies much less have grilled cheese sandwiches in a city restaurant with tablecloths and waiters. Robin and I saw a man wink at my aunt, so glamorous in her orange dress and shocking pink shoes to match her purse. My purse didn’t match anything, but it was stuffed with presents: my own personal yo-yo and a tube of pale lipstick plus a compact with powder puff. Around my neck was Jimmy’s macaroni necklace. At home, up in my room was Clark’s yellow clay stegosaurus, three especially-scribbled, torn-out coloring book pages from the twins and Georgie, and from the folks: a blue plastic transistor radio complete with dangly earplug.

Back in the hot, glittery outdoors, I still had tears in my eyes from how Cleopatra’s story ended.

Robin flung both her arms out wide. “Absolutely excellent!”

“I’ll say!” said Jimmy, blinking and squinting his eyes.

Aunt Bevy winked at me from behind her bejeweled sunglasses.

“But it was too sad at the end,” Robin went on. “Didn’t you think so, Miss Gillespie?”

Aunt Bevy nodded her beehive hairdo. “That was the best part,” she said, blowing her nose and flicking a tear from her eye with a pink-polished fingertip.

“At least poor Cleopatra died glamorously,” I said, “in her very own palace, with a serpent.” My private plan was to draw the beautiful dying queen as soon as I got home to my paper and pencils.

“How about if she just told both of those Roman guys to go soak their heads in a bucket,” said Robin. “Then she could rule Egypt all by herself.”

“There’s a thought!” Aunt Bevy exclaimed. “That’s what I’d’ve done.” She began tapping her fingers on her steering wheel keeping time with “Sugar Shack” on the radio.

Did the people in ancient Egypt and Rome know they were ancient or did they think they were modern?

Will people in the far-off future think that 1963 is ancient, I wondered? I fingered my French-braided hair, all sleek and knobby, thanks to Mom.

Aunt Bevy drove us through shadowy canyons of buildings. She pointed out her department store where she worked. “Shame we don’t have time for you kids to meet everybody.”

We wrinkled our noses at the smells of busses, cars’ tailpipes, and street pavement gone spongy in the heat. As we waited at a red light, a group of black people crossed the street in front of us. My eyes caught on the men’s thin shirts and narrow-brimmed straw hats, the women’s hats and sleeveless, summer dresses. Aunt Bevy rested her head on her hand. “I wonder how they’re all feeling about what’s going on these days in this country,” she said, more to herself than to us.

“My dad talks a lot about how people get treated,” said Robin, “just for trying to vote, or go to school or ride busses like everybody else. It’s not fair.”

“They talked about those things on the news,” Jimmy added, “and you know what Mama said?”

I nodded. “I bet she wished everyone would just be nice.”

“It’s a good idea,” Aunt Bevy said. She flicked her lipsticky cigarette butt out the window. “Whew!” she sighed, and wasn’t it hot?

***

At our house, Harry and Larry rocketed out the screen door like snakes out of a can. Darren Culpepper and Clark sat on the roof of the porch, dangling and kicking their feet. “Daddy’ gone to work,” Clark called out. “He said to tell you happy birthday, Buddy!”

“You and Darren get away from that edge, you idiots ,” I yelled, “before you fall off of there!”

“Look, Carmie, my tooth fell out!” Harry hollered, pointing at the hole in his grin as he climbed up on the curved front of Aunt Bevy’s car. “Georgie’s been a brat.”

“But not us,” said Larry. “Except Harry broke the light in the front room after Mom told him not to throw his ball in the house.”

“Did not!”

Robin, Jimmy, and I climbed out of the car. Aunt Bevy hollered up at Clark, “Say there, how’s your mama?”

“She’s okay! She’s in the kitchen cooking tomatoes and putting ‘em in jars!”

“In this heat?” Aunt Bevy’s high heels went clicking up our walk. At the sight of totally naked Georgie running out of the house, Robin and I made faces at each other. Aunt Bevy picked him up as she flounced into the house, letting the screen door slap shut behind her.

“Thanks for the movie, Miss Gillespie!” Robin called out. “Happy Birthday, Carmen! See ya later!”

Her dad, who was over locking up their front door, turned and said, “Perfect timing! We were waiting for you. I can tell you had a good time.” Mrs. Culpepper was hurrying to her side of the big, black car, cradling a covered dish in her right arm and checking her watch on the left.

“Darren!” Mr. Culpepper called, “Get your ridiculous little self down OFF that roof and come get in the car. We’re due over to Uncle Loyd’s and Aunt Margie’s.” After plenty of So long’s, Happy Birthday’s, and slamming car doors, they were gone.

When I went inside, Aunt Bevy was scolding Mama

“DeeDee, you sit yourself down, right now, over here. You look like you’re about to melt. What are you thinking of? Canning tomatoes when the whole outdoors is an oven and you’re about to pop! Are you out of your mind?”

Aunt Bevy stood tiptoe in her high heels so she could adjust the clothespins on our bedsheet curtains. She picked her way through our regular, everyday clutter of toys and coloring books to aim the window fan at her sister. It blew Mama’s damp hair in floaty curls around her face. Aunt Bevy rescued the knocked-down straw-castle, all tangled around a red rubber ball and baby tricycle handlebars, and hung it on the freshly-busted Sputnik chandelier.

“These boys have been pretty wild all day,” said Mama. “I wanted to get the canning done up before the baby comes. Did you have a good time? Everybody behave themselves?”

“Yes, we did have a good time and everybody had nice manners, but have you behaved your-SELF? No! Here you are, canning tomatoes! In your condition! As if there weren’t plenty of tomatoes in tin cans up at the store!”

Amen! That’s just what I was thinking! The mild look on Mama’s flushed face showed perfectly well that she knew Aunt Bevy wasn’t really mad at her. She petted Harry’s and Larry’s heads as they pressed their ears against her light green dress and knocked their little knuckles on her hard belly. “Come out, baby,” they called in soft voices.

“Whew!” said Aunt Bevy. “That baby might want to stay inside of you, Dee, where it’s cooler. Might as well be in the jungles of Borneo as Missouri in July!” She leaned down and kissed Mama on the forehead.

“I’ll call you later, sweet thang. Got me a date tonight. You need any help ‘round here before I take off? Anything from the store?” She slapped her forehead with her hand. “Oh for crying out loud, it’s a good thing my head’s screwed on! Carmie, run out and get me that sack under the front seat.”

Aunt Bevy dug around in it and pulled out a jar of sweet pickles and a tin of sardines. “Here you go, Dee-Dee. I hope these aren’t too cooked, being in my car all day. I know how you like ’em when you got a baby goin’.”

“Bless your heart, Bevy.” Mama smiled up at her. “I’ll have ’em for dessert tonight.”

Clark and Larry crossed their eyes and pretended to puke.

Aunt Bevy bent down and put her cheek against Mama’s hair. “Are you sure I can’t do anything for you?”

“No, no,” Mama said. “You go on. Carmen can help me with supper and anything else. Call me tomorrow and tell me about your date.”

***

Up in my room I yanked off the dress I wore into the city. I pulled on cutoffs and one of Dad’s shirts, got my drawing pad and pencils, and hurried back downstairs to grab the C book from the encyclopedia. I had to look up Cleopatra.

Jimmy lifted his own book up and out of the way so I could plop down, fling my legs across onto his lap and prop my feet on the arm of the couch. My fingers absolutely itched to draw the queen of Egypt, her snaky crown, her beaded necklace, her white gown. Would I show her on her barge on the River Nile? Too hard to draw all those rowing guys. Smooching the Roman emperor? Too sappy. Mama slowly rose from her chair as I pictured Cleopatra’s eyes, like black fishes with jewels. I’d only have to draw one of’em if I drew a side view. And I was thinking that a sideways nose was easier to draw as Mama patted one of my bare feet. The floorboards creaked as she walked past me, putting her hand on my head. “Say there, Birthday Girl, why don’t you clear off the table for me, here in a little bit?”

“Okay.”

She ruffled Jimmy’s hair with her fingers. Clark and Harry took turns clicking the channel dial making images flit and sputter across the television. Carefully, Mama walked off toward the kitchen, around Georgie’s and Larry’s block tower, the hem of her light green dress skimming the top of Georgie’s head.

Just as Jimmy turned his page, just as I was drawing a pyramid behind Cleopatra, we all jumped at the sounds of a gasp and breaking glass and the real world came crashing in on us.

The whole kitchen was red.

Mama’s back was bowed and she was holding tight to her stomach. Her other hand gripped the edge of the table. Between the freckles, the skin of her knuckles was white. Tomatoes and smashed glitters of glass were swimming in tomato-y water and a redder, darker wetness was everywhere, soaking into boxes, pooling around pots set to soak. Blood! Mama turned her streaming face to me. She grabbed my hand hard and gasped out, “The baby. Carmie, it’s the baby.”

“What do I do? What do I do!” I was almost screaming, then Mama sagged against me. It made my mind snap down to business, ice cube-cold. I shouted at the wild-eyed, blubbering boys, “Get out of here! Get away! There’s glass all over the place! You don’t have your shoes on! Out! Get OUT of here! Clark, don’t just stand there. Bring me towels! HURRY!“

Harry shouted at me, “Carmie! What’s the matter? What’s wrong with Mommy?”

“Mommy!” Bawling Georgie tried to claw his way through Larry’s legs to get into the kitchen. Jimmy’s wide-eyed face appeared in the doorway then vanished.

“She’s bleeding!” Larry shrieked.

“Shut UP!” I yelled. “Larry, take Georgie in the other room! Jimmy!” The front door slammed as Clark burst into the kitchen with a bundle of towels. “He ran outside. Did Mama cut herself?”

“Outside? Clark, can you get the telephone cord to stretch into here? I gotta call the doctor or Daddy to come home!”

“Maybe you better ought to call an ambulance!”

“Yeah, okay, bring me the phone book. Hurry, Clark! Then go – oh, I don’t know. Take the little ones upstairs and try to settle them down.” Dumb to think that anybody would be or could be calm.

I cradled Mama’s head in my lap. My shaking fingers scrambled for the right number to call when an urgent-sounding voice demanded, “Where is she?”

“In the kitchen,” said Jimmy. Hard-heeled feet came stomping through the house and Richie Scudder burst into our kitchen. Maybe if I suddenly saw Elvis Presley, I would’ve been more shocked, but I don’t see how.

Somehow, in the next crowded, horrible, five-minute-long eternity, Richie and Jimmy and I got Mama into the back seat of his old Cadillac. “We’re gettin’ you to the hospital,” said Richie, real gentle. “You’ll be okay, ma’am.”

“Okay,” she whispered. Mama’s eyes opened wide then squinched tight shut and she pressed her lips together as a hard hurt took her. Then she tried to smile at me. “Be a big girl and look after the little ones. I’m counting on you, Carmie.”

Jimmy hopped in and they roared away with Mama.

“Mom!” Clark shouted. “Goodbye, Mom!”

I ran into the street to catch Georgie. “Mommy!” he screamed. “Come back! Mommy! Don’t!” he cried, chasing after Richie’s car. I grabbed him and he struggled in my arms out in the middle of the street until the car disappeared around the corner. “Don’t go away!” he wailed. “Mommy!”

Clark turned to me, wiping his eyes with the backs of his hands. “I’ll go call Daddy at the factory, okay?”

My lips made the word “okay,” but no sound came out of them.

I felt the neighbors looking at us. Mr. Herman, his milkweed hair all white and wild, was standing on his porch steps. I swallowed hard and called to him and the Monroe ladies out in their zinnia beds. “We’re okay,” I lied. “Mom’s having the baby.”

Miss Effie cupped her gloved hands around her mouth. “Mercy!”

“You be sure and let us know what kind she has,” said Miss Lillian, “girl or boy!”

I waved and nodded my head at the ladies. Mr. Herman looked both ways then set off across the street to us as I said to the boys, real soft, “We don’t be crying in front of all the neighbors, okay?” As if crying weren’t the most sensible thing anyone could do in such a moment. I lied to them too: “Everything will be all right.”

Georgie buried his face in my neck and Larry sniffled. With the back of his hand he dashed away his tears, like he was too big to be crying in front of Mr. Herman. Harry, with his thumb in his mouth, wasn’t quite so proud.

“Now there,” said Mr. Herman, crinkling his eyes at me. “I wasn’t spying and I don’t like to barge in on you just when you’ve got your hands full.” He shifted his cane to his other knobby hand so he could pat Larry’s shoulder.

“I just happened to see the way your little brother. Now, James didn’t come to me. He knew I didn’t have no car no more! Then that wild Scudder boy went tearing off with your mom and the way them little fellers were carrying on. I could see that you were having a bad time. You say the baby’s comin’?”

“I think so.” I gulped. “Thank you for...you’re really, really nice to come check on us, but...”

I thought Mr. Herman was searching his pockets for peppermints, but instead he dug out a bent calling card and held it out to me. “This here’s got my phone number. Now, you call if you need any – I mean any little thing. You fellas help your big sister, okay?”

“Okay, Mr. Herman, we will,” said Clark, in a way that made me think I wasn’t the only one who was thinking just go away and quit being so blasted nice before I start bawling in front of you. We’re in terrible trouble and I can’t even stand to think how much help we need. I

herded the boys into the house and leaned my back against the closed front door.

“I told a guy at Dad’s work to tell him about mom,” said Clark. “Do you think he’s at the hospital now?”

“Probably. He’ll call us any minute now, I bet, to tell us about mom and the new baby.” I put an arm around Clark’s bony shoulders. “You wanna help me …uhm… let’s clean up the kitchen a little bit, okay?”

Clark and I attacked the splintery mess. I stuck Band-Aids over the places we’d cut ourselves. Beside the sink was Mama’s gift from Aunt Bevy. Dumb how that stupid tin of sardines made me feel even more terrible. I stuck it in a cupboard and went down to the cellar. I plunged the stained towels into the washtub, pulled my shirt over my head and pushed it in too. Blood moved like red smoke, like mermaids’ hair in the water. I shivered and rubbed at the goosebumps on my arms. Why hadn’t Jimmy or Dad or anybody called from the hospital?

The soft thumps and voices of the television and the boys sifted down through the ceiling beams. From Mama’s rainy day clothesline, laundry hung like a row of ghosts in the gloom. I yanked off a shirt and put it on, then, like Mama probably used to do, I stood listening to the sounds of everyone’s voices and footsteps up above the dangly wires and spiderwebby house beams. It was comfortable, in a strange sort of way, to hear everybody from this little distance. Down here, away from them all, you could appreciate the idea of our family. It felt like a glimpse of the mom I hadn’t known, like I understood her better, somehow.

What was happening to her? What were they doing to her?

I headed back up the cellar steps, away from the rush of feelings that came with my memory of Mama’s face and what she’d said to me.

All of the boys were scattered about the front room, each with cereal bowls full of ice cream. “Ice cream always makes things better,” Clark said meekly.

I smoothed his hair. “Good idea, kid.”

“Mom got it to go with your birthday cake,” said Harry. An almost empty ice cream box was leaking all over the table. I popped a spoonful of it in my mouth and put the box in the freezer and the phone rang.

Clark won the scramble of ‘I’ll get it’s’. “Daddy? Okay, okay, here she is.” He scowled. “He just wants to talk to you.”

I grabbed the phone away from him. “Is Mom okay?”

“Carmen?” Dad said, “Is that you?” I could hear people talking in a busy background. “Well, we got us a baby.”

“How’s Mama?” My question collided with Dad’s news. I blew out a big breath and told the boys, “Mama had a girl!”

“Yuck!” Larry shouted, wrinkling his nose in mock disgust at Harry who clapped his hands. Clark stood staring at me, worry frozen on his face while Harry, Larry, and Georgie kept pulling on me and pestering me. “When’s Mommy coming home? Lemme talk to her! Lemme talk!”

“Be quiet, you guys!” I stuck a finger in my ear so I could hear Dad say, “Carmie? Are you all okay?”

“Yeah, we’re fine, but you didn’t tell me how’s Mama? Are Richie and Jimmy there?”

“They’re right here. That Scudder boy’s gonna bring Jimmy home in a little bit, but, listen honey, I gotta go. Your mama’s not …he’s not doin’ so good. Now, the baby’s fine; she’s just perfect, but...“ I heard Daddy clear his throat.

“What?”

“Now Carmie, I got hold of Beverly and she said she’d stay there with you all tonight. The baby hadn’t showed up yet so Bevy doesn’t know. You go on and tell her and...oh, I don’t know.” I gripped the phone tighter while Daddy paused. “It, uhm --it may be late before I can get home.”

My whole insides felt like a cave full of bats. My face must’ve been pretty scared-looking because even Georgie piped down. “Daddy? Don’t go!” I pleaded. “What’s the matter?”

“I gotta go, honey. They’re callin’ me. Say your prayers.”

He hung up and so I did, too.

If things were normal around our house, if I wasn’t needing to be here with the boys, I’d have run upstairs to my room and closed the door. Of course, if things were normal, I wouldn’t be standing by the phone trying not to cry in front of them because Mama would be here. But she wasn’t and things were rotten.

It wasn’t much later when Clark ran to the window. “Aunt Bevy’s here!”

The boys followed her in the door. Her makeup was smudged and her beehive hairdo had come loose since she’d taken us to the movies way back a million years ago.

“I just got in the door when your dad phoned,” she said, sounding out of breath. “I didn’t even call the fella I was supposed to go out with tonight I speeded all the way back over here and I think I ran a red light! Carmen, what on earth –? What happened? Has your mom had the baby?”

TelIing Aunt Bevy made me see everything all over again in my mind. “It was right after you left. In the kitchen – Mom was bleeding. She was hurting real bad.” I choked out the words and couldn’t stop a tear from rolling down my cheek. “It was because of the baby.”

Aunt Bevy pulled me to her in a hard squeeze.

“It’s a girl,” said Clark. “That’s what Dad said.”

I heard Aunt Bevy say, “Oh my!” and my own thick voice:

“He said to say our prayers.”

I pulled away from her, wiping my eyes, but Aunt Bevy kept tight hold of my hand. She pursed her lips and looked at all of us Cathcarts, then, for a little bit, down at her pointy-toed shoes. She stepped out of one high heel then out of the other, pushed a toy truck aside with her stockinged foot, and knelt down on her knees on our front room floor. With a twirl of her hand she motioned for us to kneel down beside her.

“Fold your hands,” I told the boys, “and close your eyes.” Aunt Bevy’s hoarse voice began, “Our Father, who art in Heaven...”

It was late. The ten o’clock news had started and Robin’s family had come back home from visiting their relatives. Lights were on over there. It seemed strange that Robin was right next door and didn’t know yet that anything was wrong. Aunt Bevy and I had gotten the little kids in bed. A car stopped out front.

Two doors slammed. I saw Jimmy and Richie get out and come up the walk, their heads bowed-down tired. They climbed the steps into the moth-flutter around the porchlight. It glowed on Jimmy’s glasses, then haloed Richie’s summer crewcut. His eyes darted around at all of us as he followed Jimmy into the room. My eyes kept going to their blood-stained tee shirts.

Without a quiver, without even a ‘hi,’ Jimmy looked at me hard and said, “I think Mama’s going to die.”

“What?” I looked over at Richie, then back to Jimmy who wouldn’t answer me, just headed up the stairs. “What?” I pulled at his shirt. “Did the doctors –? Did Dad tell you that?” I sputtered, grabbing his arm. “Did you hear the nurses say something?”

He only frowned and scrunched his head down and away from me, like I was hitting him. “I don’t know! I just think she is! Leave me alone!” He yanked his arm away and trudged up the stairs.

Aunt Bevy had been sitting on the couch with sleeping Clark using her lap for a pillow. Now she struggled out from under him to follow after Jimmy. Richie glanced at me from under his eyebrows as he stalked out of the house. I ran to catch the screen door before it slammed. “What happened?” I called after him.

He stopped in the middle of our cracked walk and rubbed the back of his neck before he turned around. “They all seemed kind of worried and runnin’ around, I guess,” he said. “Look, I ain’t no doctor, kid.”

Richie seemed different, kind of older, somehow, than before. Maybe it was because now I knew more about him. Plus he’d helped Mama. I followed him to his car. “Thank you for all…” I leaned down so I could look at him through the passenger window. “Thank you for all you did.”

He started up the car and turned on the headlights before he spoke, without ever once looking me in the eye. “Yeah, well, I was just glad the kid came and got me. Must not’ve been anyone else around with a car.”

“He must’ve thought you could help.” I rested my hand on the car door. I started to say ‘Imagine that,’ but it’d sound too dumb.

“Anyway,” he muttered, “maybe it made up, kind of, for that trouble with the dog and all...“ He gave a little snort. “Oh yeah, your kid brother said it was your birthday.” Real quick, he directed his eyes at mine then back to the lit-up dashboard. “Some day, huh?” His hand reached itself toward mine, like people do sometimes: pat your hand, comforting-like. Just in time, he snatched his hand away and said, “Look, I hope your mom’s okay.” Then he jammed his car into gear and I jumped back. Richie Scudder roared up the black street away from our house and he screeched around the corner, and the sound of his engine faded into the night.

I sat out on the front steps, leaning against the porch post. I looked up and down the quiet street at the porch lights and gleams of light shining through whirring window fans. Mr. Herman’s bungalow was dark. So was the house where the Monroe ladies lived. The treetops were blowing black in the cool night breeze, like God was breathing down, like guardian angels were fluttering their wings.

‘Sometimes things go wrong,’ Mama had said. Please, please, I prayed. A sharp smell of cigarette smoke interrupted my memory and my hoping. Aunt Bevy had turned off the porchlight and come outside.

“Did you call over to the hospital?”

“Just now.” She paused. “The nurse said that your father’s on the way home.”

“What else did she say?”

I couldn’t see her face. She was just a construction paper silhouette against the front room window. The spark at the end of her cigarette flowered orange as she inhaled more smoke. “What did she say?” I asked her again, louder this time, and I held my breath. My face felt cold.

Aunt Bevy wiped at her eye with the heel of her hand, like Georgie does when he needs a nap. She sniffed and I heard a soft sob come from her throat. Another sound made me turn to see Jimmy at his bedroom window. Headlights came around our corner. Our old Rambler shot up the driveway, then the engine fell into a deep, humming sort of silence. You wanted to hold onto such a quiet.

Saturday, February 11, 2012

What knocks me out about Thos. Edison...

"Be courageous. I have seen many depressions in business. Always America has emerged from these stronger & more prosperous. Be brave as your fathers [and mothers] before you. Have faith! Go forward!"

Friday, February 10, 2012

'Tis the Season to be Freezin'

"Antisthenes says that in a certain faraway land the cold is so intense that words freeze as soon as they are uttered, and after some time then thaw and become audible, so that words spoken in winter go unheard until the next summer." ~Plutarch, Moralia

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

celebration

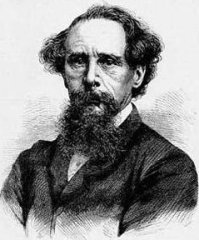

So. The sun has gone down and the 7th of February, the 200th anniversary of the day that Charles Dickens launched his life of troubles & glory; the 145th anniversary of the birth of Laura Ingalls [must've been mighty chilly in that little h. in the big w.] is nearly over and how did I celebrate it? Well, I read a bit of A Tale of Two Cities on my Kindle whilst waiting at the local post office. Does that count?

Monday, February 6, 2012

Just For You to Know: Chapter SIX

To those of you who chance upon this posting, allow me to note that this

To those of you who chance upon this posting, allow me to note that this JFYTK: Chapter Six

In which we learn something horrible about Richie the Creep.

Mama and I stay up late on the night of the last day I’ll ever be

twelve;she and I get better acquainted.

“What’d she mean?” Jimmy asked. “Are you and Robin going to the movies?”

“Maybe. Aunt Bevy said she’d take us for my birthday.”

“I wanna go.”

“I don’t think so.”

Wasn’t it bad enough that Old Yeller might not let Robin go with me and Aunt Bevy? Did I want to share my birthday with a little brother? Not exactly.

Jimmy stomped up the steps behind me and let the screen door slam. “Robin’s my friend too!”

“Hush up!” Dad said. He jerked his thumb at Mom sleeping on the couch. “Jimmy, you clear the junk

off the table and Carmen can peel some taters while I open up some cans and rustle up supper. Your mama’s not feelin’ good.”

***

When I was up high enough to look over the edge of the boards in the tree, an eerie moonface floating in the branches spoke to me: “It is eight minutes after midnight.” Then Robin switched off the flashlight under her chin and helped me up into her office.

“You are so weird,” I panted. “Did Aunt Bevy call your mom? I called and asked her to. Did your mom say you could go?”

“Your aunt called and mom said that she and Dad would think about it.”

“Well anyway, I’m glad you’re here and not in Minnesota.”

There didn’t seem like much else to say. We lay on our backs, feet propped in the branches, eating our strawberry cake. Our street was dark and quiet until a sound like a creaky screen door broke the stillness.

“What was that?” I whispered.

“I didn’t hear anything.” But she couldn’t help hearing what came next: an angry rumble of voices from the Scudder house. Yelling, too far away to hear all the words, close enough to hear the meanness.

“It’s Richie’s dad,” Robin said under her breath.

“Huh? You think we ought to go see what’s happening?”

“I know what’s happening. Ever since Mrs. Scudder died, he gets real noisy sometimes.”

“When did she?”

“Two or three years ago. Richie was in ninth grade, I think.”

We heard a twig snap, then footsteps down below! Robin grabbed her flashlight, but she didn’t need it. The streetlamp and a couple of porchlights were enough for us to see who it was.

“Hey, Jimmy! Stop!” We shouted as loud as we could and still be whispering, but he just kept walking in the direction of Richie Scudder’s house. Boy, I’d never gone down that stupid rope ladder so fast! Robin and I hurried over to the blackest shadows, by Mr. Scudder’s pickup truck. Only the sound of breathing and a glint of light on his glasses told us that Jimmy was there, too. Now the three of us jumped at the sound of a man’s voice, ugly and angry.

“I’m glad your mother’s not around to see what a bum you turned out to be!”

“This is dangerous,” I hissed, but still, we kept inching through the dark, like trouble was a magnet.

“Listen, old man, I got a job,” we heard Richie say.

“Don’t you sass me, boy!” Mr. Scudder thundered. I felt more than saw Jimmy’s shoulders cringe when we heard a thump and hitting-sounds.

“Stop it, man, you’re hurtin’ me!”

“You’re gol-durn right I’m hurtin’ ya, you lazy worthless --”

“Come on,” I hissed. “We shouldn’t be here.”

“His dad is so mean,” Jimmy whispered when we were back in our yard. “Still...Richie was rotten to do what he did to Cracker. She was just a poor little dog.”

“Yeah, well, maybe his horrible dad is why Richie’s so creepy,” said Robin.

The night was quiet again, like Richie’s crummy dad had settled down for the night. I wished ours had when he caught Jimmy and me sneaking in.

“Don’t even tell me what you’re doing up at this hour,” said Dad. “I don’t want to know. It’s too danged late.”

“Why were you out there, James?” I asked, when it was just us. “You were spying on Robin and me, weren’t you?”

You wouldn’t think a person could yawn and push his slippy glasses up and still look sly, but Jimmy could. “I just wanted to see if Robin can go to the movies with us,” he said.

***

Almost all of the night before I turned thirteen, I couldn’t sleep. Maybe, if I weren’t so excited about Robin’s mom giving in and saying she could go to the movies, I could’ve slept, if it weren’t so hot and sticky. My eyes kept opening and seeing pale rectangles. All around me, thumbtacked to the walls and ceiling were all of my lady drawings. They were so beautiful. It was nice, knowing they were there, and fun, imagining them talking among themselves when I was away. Their gowns fluttered in the warm breeze from the worthless window fan, which couldn’t cool one single inch of my bed. My pillow felt like a hot water bottle and besides, I heard voices downstairs.

Avoiding the creaky places on the stairs, I tiptoed down and past my parents’ empty bedroom and the boys’ room, and on down until I could tell where the voices were coming from the television. It had been turned so it could shine out of the open front window. Beyond it was the only-slightly-cooler outdoors, the porch swing, and Mom, watching the late movie.

I slipped out of the front door as quietly as I could, but the spring on the screen door squeaked to let her know I was there. Mom patted the swing beside her and, with a glance at her belly, whispered, “This child can’t sleep either.” She breathed in a couple of shallow sips of air. “It’s probably as warm and humid in there as it is out here, poor thing. Well, we can watch the movie together and tell

Daddy hello when he comes home from work.”

I returned Mom’s smile in the dark. “He’ll like that,” I whispered. We almost never got to be just us two, Mama and me. The chains squeaked and protested as I sat down next to her.

“Goodness,” Mama said, stroking my hair, “look how long this has gotten. We’ll want to trim those bangs before Bevy comes tomorrow. Maybe you’ll let me French braid it like I did when you were little.”

Her hand felt nice, but I had my private doubts about bang-trimming and braids. Moms can do some weird damage when they start messing with your hair.

“It’s your Birthday Eve!” she went on. “There should be a custom for that, don’t you think? Like hanging up a stocking?”

“We could leave cookies and milk for the Birthday Fairy.”

Mama chuckled.

“Or,” I suggested hopefully, “I could open my presents after midnight.”

“In the morning,” she told me, “like a proper birthday. And I saved an extra present, for Saturday when we have your cake and candles.”

“What is it?”

“A surprise that’s what. Shush, now. You’ll want to hear this movie. It’s National Velvet.”

We’d been whispering like I imagined girls did when they stayed all night at their friends’ houses. Moths and June bugs were fluttering, hurling themselves at the window screen, crazy to get at the glowing pictures of a dark-haired girl (“That’s Elizabeth Taylor,” said Mama.) and a running horse. The night was dark and sweet-smelling, like the inside of a lady’s black velvet purse. A cool breeze ruffled through the trees. When the movie gave way to a commercial, Mama began whispering again.

“I’m glad they’re showing this. My mom – your grandma – took Bevy and me to see National Velvet when I wasn’t much older than you are now. It was my favorite.” According to Mom, this old movie was about more than Velvet Brown and Pi, her horse, and their winning a big race. “It’s about Velvet’s mother there, and how she and her daughter shared their dreams. They both had high hopes.”

“What were your high hopes?” I asked.

“Well...”

“Did you have a dream?”

“Oh.” Mama paused. “Well you know, your father and I… when he got home from the war and we got married...well, we wanted you children. I guess you could say that was our dream, a nice big family.”

It sounded like a nightmare to me. “Why?” I interrupted.

Even in the darkness I could see she looked surprised. “Babies are a gift from God!” she said, a lot more firmly than she usually talked.

Not much of a present was the thought that popped out of the bratty part of my brain. Another crybaby thought tumbled right out after it: Each new kid only pushed her further away from me, from the time I was her only one.

“Why did we have to have such a big family?

I mean, we could have just been Jimmy for Daddy and –” I was ashamed to say the babyish rest of it: And me for her. I had some pride.

Mama pressed her cool hand to the side of my face. “Oh Carmen,” she said, ignoring the movie that had started again. “How can I tell you how it was for your dad and me? The war and the Depression years before that, when we were kids, they’d been so hard. So when I first found out that I was....“ Mama’s hand rose to fiddle with her hair. “When I was going to have a baby, we were so happy, but then something happened and…” Her voice faltered. “And, well, I lost the baby.”

“Lost it?” My own voice was small. Of course I knew she hadn’t misplaced the baby or left it somewhere. I couldn’t stand to think of her being sick or in trouble.

“It was a medical thing,” she went on. “Things… pregnancies, I mean, sometimes go wrong. We were both so sad, and then, when it happened again –”

“Again? That happened to you two times? That there wasn’t going to be a baby after all?” I squeezed her rough hand.

“It was almost worse for your poor dad,“ said Mama. She looked out into the night, as if she could see him out there, with his head in his hands out in some long ago, far-off yard. “Then you came along.” She smiled. “You were so cuddly and happy. You were a dream-come-true.”

Her words made my throat tight and tears sting my nose. Okay, I was pretty desperate for her to say something mushy like that.

“And even on your worst day, you still are.” She put her arms around me and hugged me to her big softness. Mama smelled like face powder, baby powder and graham crackers. “This baby will be a dream-come-true, too. You’ll see.”

Dad’s headlights swooped around the corner as the movie ended and back inside the house, our clock chimed midnight. Mama hugged me even tighter and told me, “Happy birthday, Carmie.”